Recently, the rapper and actor Ice Cube has stirred quite a commotion by his association with the Trump campaign, who contacted him to discuss his Contract With Black America. Many African Americans on the left have attacked him or belittled him on grounds that he was attempting to split the Black vote, he was being used by the Trump campaign, that his plan was misogynistic, that he was oblivious to the work of other activists as well as Biden’s Lift Every Voice Plan, not being articulate enough, etc.

While it is possible that these critiques are true, they serve to divert attention to the merits of Ice Cube’s content and strategy. Anyone who has followed him on Twitter since July (or the 1990’s) is aware of his political positions. He has unequivocally expressed his disillusionment with both the Republican and Democratic parties, while maintaining a pragmatic view of political engagement. One that allows him to work with whichever party wins the election.

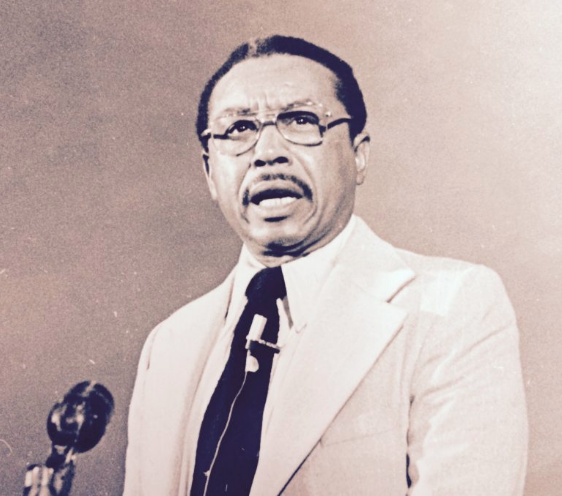

This political pragmatism is not new. In fact, Ice Cube’s strategy is reminiscent of that of Floyd McKissick during the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. McKissick was a lawyer from North Carolina and a Civil Rights leader. He was one of the first four African American students to desegregate the law school at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC). Although he was renown in Civil Rights circles ascending to the head of CORE in 1966, he was part of the contingent who advocated for Black Power. He hosted Malcolm X at UNC after he was rejected to speak at the predominantly Black North Carolina College (now North Carolina Central University). He also associated with the likes of Kwame Toure (Stokely Charmichael), Ron Karenga, and Martin Luther King Jr.

In the spirit of African resistance in the Americas, he revised the notion of Maroonage in the post-Civil Rights Era with his establishment of Soul City in rural North Carolina. The city was to be a model of how African-Americans can circumvent the struggles of acquiring political and economic power in existing urban areas where the odds are already stacked against them by establishing their own cities from scratch. In order to achieve this goal, he sought the help of the federal government to pass the Urban Growth and Community Development Act, which would secure funding from the Department of Housing and Urban Development for this and similar projects. He and those that followed him made a strategic alliance to support the election and re-election of Republican president Nixon.

This was a controversial move even in his time. We know that the Democratic Party, prior to the 1960’s, was the party of the Ku Klux Klan and White segregationists. However, it was the policies of presidents Kennedy and Johnson that caused them to shift to the Republican Party. Yet, this shift was still new and tenuous by the 1970’s and African Americans overall were more politically conscious than ever. Party loyalty rhetoric was at a minimum because many African Americans in the South had just overcome the Democratic and Republican parties’ Jim Crow restrictions to their right to vote.

The Democratic Party later became known as the party of Civil Rights because they passed a series of Civil Rights bills. Nonetheless, politically conscious Black people knew that the bills were the death knell of the movement or at the very least an amicable diversion from the goals they sought to attain. Integration was not the same as desegregation. Integration allowed for Black people to join the White economic, social, and political establishment – at the bottom of course. However, desegregation was aimed at releasing the yolk of Jim Crow and post-Reconstruction Era measures to suppress Black economic, social, and political power. In other words, they aimed at restoring the Black power that would have naturally existed without racist intervention to suppress it.

I see the Contract With Black America as a means to revive the spirit of Black Power that has lain dormant since at least the 1990’s. Ice Cube has been vocal that his plan for Black American descendants of enslaved people and not broader categories such as “people of color” or “minorities” that could divert funds from them. He has explicitly criticized the Republican and Democratic parties, while being open to work with whichever party wins the election. Furthermore, he has called for Black people not to depend on campaign promises and lip service, but to put political pressure on the victors well after the elections. I personally do not see anything wrong with this perspective. Rather, it sounds like a plan.

One characteristic of the Trump Years has been the stark polarization that his presidency has forced the American public to take. This has clearly taken place within the Muslim community with the rise of the “Akh-Right” and “Social Justice Warriors.” Likewise, this has taken place within the African American community with more aggressive Black conservatives and more staunch Black liberals. As they mudsling during the election season and attempt to recuperate in its aftermath, I commend those Black Muslims with major platforms like Ice Cube and Dave Chappelle who are still thinking clearly in the mist of hysteria.