I began writing this piece in the Fall of 2024, prelude to the U.S. presidential elections. At the time, much of what we already know about the Zionist predator, Jeffrey Epstein, had already been uncovered. However, the recent publishing of the Epstein Files has served as direct evidence of his degenerate crimes and the plot of the modern Mystery Schools. I think the publishing of these thoughts are timely.

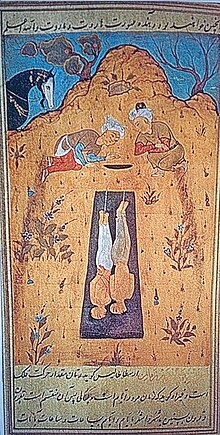

American elitism is on its last leg. Anyone paying attention to national and international events can clearly see that America will be heading a different direction than the status quo in this third decade of the 21st millennium. While we think of elites as those in control, they are more accurately described as those controlled by the mystery rulers. Their behaviors and traits have been consistent throughout history. They performed rituals and stirred up mischief for the jinn of their locales. With that, they were able to maintain power until an appointed term.

وَأَنَّهُ كَانَ رِجَالٌ مِّنَ الْإِنسِ يَعُوذُونَ بِرِجَالٍ مِّنَ الْجِنِّ فَزَادُوهُمْ رَهَقًا

Some men among the humans would seek refuge with men among the jinn, who would increase them in wickedness (al-Jinn: 6)

In 2006, comedian Dave Chappelle appeared on Oprah Winfrey’s show to discuss why he turned down a $50 million deal with Comedy Central. On this show, Chappelle would make an infamous insight into Hollywood culture that would eventually lead to the breaking of the spell Hollywood has had on people. Chappelle’s story about being pressured to wear a dress in a movie would linger long in the memory of popular culture. Innocently introduced as a possible “conspiracy,” the mere suggestion of a Hollywood cabal hell bent on the feminization of Black male celebrities was not hard to believe after seeing countless movies of otherwise heterosexual actors playing roles that seemingly compromise their sexuality. Over the years, layers of this “conspiracy” would manifest to the public piecemeal, but never in its full light… until the recent release of the Epstein Files.

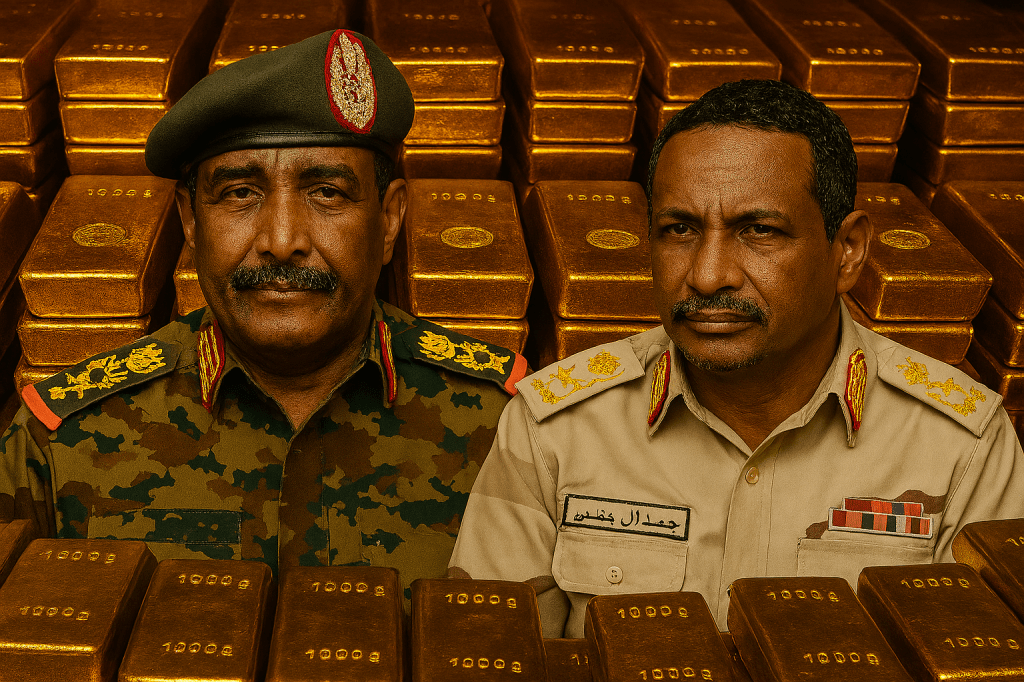

I contend that the world’s elite maintains their “powers” over the majority of mankind by appealing to the jinn through sex magic orgies and ritual sacrifice. As I mentioned in From Darkness to “Polight”: A Prospectus on Sabianism and Ritual Sacrifice, “These jinn promise them the fortune, fame, pleasures, and power that they seek, but demand that they perform disgusting and evil acts as devotion to them. These acts usually involve violating children, whether it’s rape, mutilation, or murder.” Although the Epstein Files, the law suits and criminal trials of Sean “P. Diddy” Combs and Mike Jeffries have given the public a good look into the sick actions of the political, entertainment, and intellectual elites, they have never succeeded in answering why they are blackmailed with salacious, perverted, and sometimes illegal acts. These cases mirror what’s happening internationally. Just as the U.S. elites are collapsing on themselves, so is imperialism in the form of Americanism and Zionism.

Scandals of the 20th Century: Leadbeater and Theosophy

We know that the Theosophical Society (TS) in America started with the charlatans Helena Blavatsky and Henry Olcott. Yet, a second generation of TS members would continue it and popularize its ideas in the West. One such person was Charles Webster Leadbeater, a central figure of the so-called “modern occult revival” in the early 20th century. He is the reason that words like karma and chakra found their way into our everyday vocabulary. He is also credited with popularizing ideas around reincarnation, “energy,” “vibes,” vegetarianism, a return to nature, the long-hair hippy aesthetic, and mind reading.(Tillett, 1982, pp. 1-10)

Despite his heavy influence on popular spiritualism, he had a darkside. His career was plagued with accusations of pederasty and sexual perversion. The first allegations appeared in 1906 after a boy once in his care cut off communications with him. The boy’s parents, noticing this, learned that Leadbeater and their son slept naked in the same bed and he taught the boy how to masturbate. Leadbeater justified his behavior by claiming to see “sex feelings” in boys’ auras and at this point teach the “esoteric” practice of masturbation, in order to curb their “unnatural” sexual desires towards the opposite sex.(Tillett, 1982, pp. 77-81) His colleagues in the TS would even notice how rude he was to women, refusing to talk to them or shake their hands. Yet Leadbeater seemed keen on grooming an elite Brahmin-like caste within the society made up of young men in their teens and early 20’s.(Tillett, 1982, p. 160)

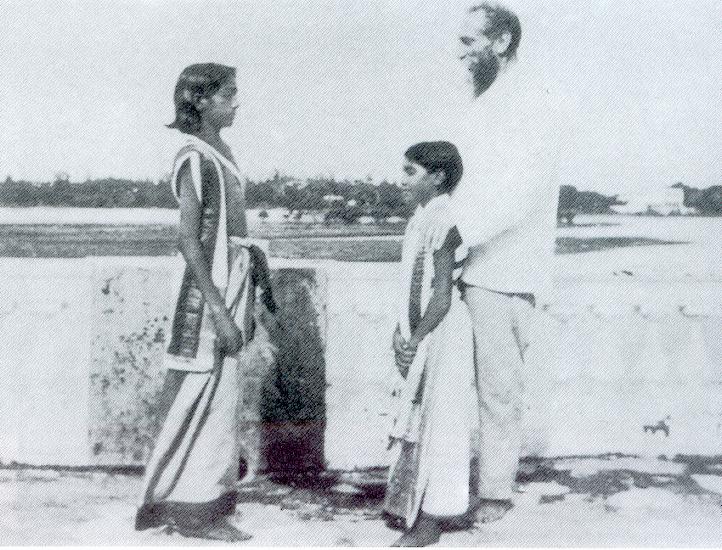

I must also note that Leadbeater’s Theosophical work was part of Britain’s colonial project in Adyar, India. His role in “educating” young Indian boys and separating them from their families is well documented, especially with regards to Jiddu Krishnamurti. Krishnamurti was the son of a man who worked for the Theosophical Society. The boy was hand-selected by Leadbeater for spiritual instruction after being “especially attracted” to him. He believed Krishnamurti to be the next great Theological teacher of the time, which the boy would disavow in his adulthood.(Tillett, 1982, pp. 103-104)

Photo credit: Krishnamurti Foundation Trust

Epstein and the Transhumanist Scandal

Fast forward almost a hundred years, we caught another man among the “transhumanists” seeking refuge with men among the jinn increasing people in wickedness. The case of Jeffrey Epstein was not the first of its kind, but it was monumental for this century. It has exposed the political and academic elite and their links to intelligence agencies not only in the US, but around the world. Oddly enough, his former friend, President Trump, in his first administration, would make this case mysteriously disappear. Jeffrey Epstein would commit suicide as he awaited trial in a Brooklyn jail or so the story goes.It is clear that Epstein and his handler Maxwell were working for intelligence, most likely Israeli, to blackmail elites from around the world. Indeed, no one could truly be an elite without attending an Epstein party which was known for its sexual violation of young girls.

When his Palm Beach, FL home was raided in 2005, police found numerous recordings (including CD’s marked “Happy Birthday” – a theme in the Diddy case as well) and erotic material (including photos of naked underage girls).(Howard et al., 2019, pp. 104-106) He was later convicted of child prostitution in 2008 and subsequently, not too many of his old political fans wanted to be associated with him publicly. In an interesting turn of events, he began to make friends among the academic elite and managed to ascend to positions at Harvard and MIT.

Despite his high profile in his final years of public life, much is left unsaid about Epstein’s beliefs and motivations. For instance, he was a champion of transhumanism, which is essentially the idea that human beings, particularly the ruling elites, can live forever. Julian Huxley, a British eugenicist coined the term and initiated research and writing on this topic. Oddly enough, he was also credited with coining the term “agnostic.” He was the brother of the famed author, Aldous Huxley, who popularized Theosophical ideas for Western youth culture.

While transhumanism sounds like the fantasy of some cartoon super villain, Epstein strove to make it a reality. As early as the 2000’s, Epstein was known to have said: “Your body can be contained. But not your mind.” Not only this, but he planned to deep-freeze his head and penis for a future resurrection. Additionally, he also wanted to “strengthen the Earth’s gene pool“ by impregnating multiple women in some sort of “baby farm.” (Howard et al., 2019, page 183-184) Beyond the sick fantasies, he would provide multi-million dollar gifts to the Program for Evolutionary Dynamics at Harvard and to MIT’s Media Lab (some allegedly funneled through Bill Gates) and rub elbows with scientists to further this aim.(Howard et al., 2019, pp. 185-188)

Following his conviction and release from prison in 2010, members of high society threw a party in his honor featuring notables like Katie Couric, Charlie Rose, Chelsea Handler, Woody Allen, George Stephanopoulos, and Prince Andrew.(Howard et al., 2019, p. 173) It was at this time that Epstein began to rebrand himself as an intellectual and philanthropist. The husband of Ghislaine’s sister, Isabel, was a visual theorist by the name Al Seckel. He arranged the “Mindshift” conference with Epstein on St. Thomas and Little St. James.(Howard et al., 2019, p. 175)

Seckel would eventually have a “falling out” with Epstein before falling off a cliff on a hiking trip in France. At the time of his death, Seckel was attempting to sell documents related to his Mossad-affiliated father-in-law, Robert Maxwell, to no avail.(Howard et al., 2019, pp. 176-178) From that time on, we can track Epstein’s affiliations with the intellectual elite in the government files. While much is said about his island, Little St. James, very little is said about his 10,000 acre Zorro Ranch near Sante Fe, New Mexico. Of course, workers on the ranch were instructed to keep silent about what they saw there, but this is where he harvested his connections to the scientific community.(Howard et al., 2019, p. 178)

Nevertheless, this conference introduced Epstein to a different kind of elite. This elite class is what Guenon referred to as the spiritual/intellectual elite who have gained ranks in the Lesser Mysteries. Guenon, however, had little confidence in the Western version of this class of people, who, as a matter of principle, separate the material from the spiritual and the physical from the metaphysical. As such, many of the prominent scientists in “artificial intelligence, emerging technologies, new trends in theoretical physics, and a host of other highbrow topics” flocked to Epstein’s perverted island to rub elbows and other organs in search of funding for their respective projects and institutions. The Mindshift Conference of 2011 was in part organized by AI-pioneer, Marvin Minsky, who Virginia Giuffre serviced at the behest of Epstein according to her testimony.(Bartlett, 2019) He supposedly died in 2016, but like his buddy Epstein, wished to have his body frozen. With all the hype about Generative AI, artificial super intelligence, and the rise of the Technocracy, it is not difficult to connect the dots.

Conclusion: The Emperor Has No Clothes

It appears that the cloak of elitism is no longer needed now that the New World Dajjal System has established its tentacles in most aspects of daily life. From ancient Sabian priests to theosophers and the Epstein class, the so-called elites were only a veil for the jinn they served. They denied the existence of a master class or a conspiracy, but the veil has been removed and they are nervous about what the people will do. Will the people allow them to carry out their plan and let them live forever as they hope or will the people hold them accountable for their actions in this world and let God hold them accountable in the next?

In order to understand Epstein’s role in the construction of the so-called New World Order, which is nothing less than the changing of an epoch, we must refer to some of the insights offered by Rene Guenon (Abdul Wahid Yahya). In ancient times, leadership lay in one of two camps: the intellectual authority who learned, preserved, and taught the spiritual and intellectual traditions to the people, and the governing power who enforced order through administrative, judicial, and military means.(Guenon, 1929, pp. 16-18) The forces behind Epstein understood that the corruption of the two spheres of intellectual/spiritual authority and governing power gave them freedom to act with impunity. Public exposure was once their worst nightmare but now that it’s happened will you bring that nightmare to fruition?

References

Bartlett, T. (2019). We Dug Up Jeffrey Epstein’s Old Science Blog. It’s as Weird as You Think. Chronicle of Higher Education, 66(1).

Guenon, R. (1929). Spiritual Authority and Temporal Power (H. D. Fohr & S. D. Fohr, Trans.). Sophia Perennis.

Howard, D., Cronin, M., & Robertson, J. (2019). Epstein: Dead men tell no tales : spies, lies & blackmail. Skyhorse Publishing Company, Incorporated.

Tillett, G. (1982). The elder brother: A biography of Charles Webster Leadbeater. Routledge & K. Paul.