The images of horrific killings and explosive clashes currently shattering El Fashir and Kordofan are not simply the sights of a localized power struggle between two warring Sudanese military factions, they are the visual symptoms of a new global African Gold Rush. There are ideological or ethnic divides, but the big picture shows the usual suspects of multinational corporations and imperialist interests meddling behind the scenes. Sudan is but one site in the a multi-billion-dollar, transnational exploitation collage where natural resources are being siphoned off to power Big Tech and provide an insurance policy against the looming instability of Western currencies. In this post, I will discuss some of the actors driving the war in Sudan and their interests and how we in the US are complicit in it.

Actors and Interests

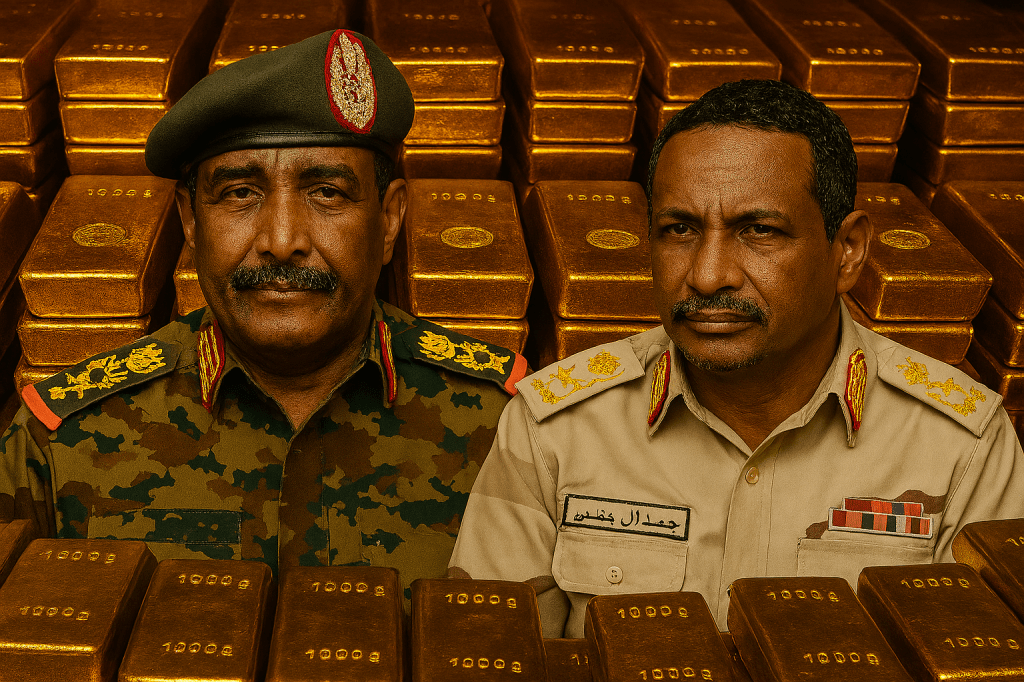

Two men stand at the center of the Sudanese conflict: General Abdul Fattāḥ al-Burhān of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and Muḥammad Ḥamdān “Hemedti” Dagalo of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). Once friends, and fellow war criminals, the two men previously served as henchmen for former president ʿUmar al-Bashīr. Hemedti was a leader within the mercenary forces known as the Janjaweed, who in addition to massacring hundreds of thousands of Darfurians, also fought against the people of Yemen and Libya.(Booty et al., 2025) Hemedti also became rich by controlling several gold mines in Darfur. While the two men were able to share in the overthrow of Bashīr, they were not able to share in their mutual avarice for power. Despite the people’s ardent rejection of military rule, the two men decided that their personal interests were more important than the will of the people. So they dragged the countrymen into a prolonged war to decide who will be the next leader of the Republic of Sudan.

In the words of Donald Trump, Sudan is just another sh•thole African country. So why would these two men fight over power in a country that has nothing? Again, the gullible American people have been lied to. Not only are states like Sudan, Niger, and Congo rich in minerals, they serve as the backbone of many American and European economies. Without them, the West would be full of… well… sh*thole countries.

This is the dark side of globalization that we used to hear about some 30 odd years ago. Every year, as much as $35 billion worth of gold produced by artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) in Africa goes undeclared and is smuggled out. Between 80% and 85% of this illicit gold finds its way to the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which acts as a “golden gateway” of ill-gotten gold to the so-called legitimate world. (Soguel and Turuban, 2024) Apparently, owning gold mines is the secret to funding a paramilitary group which can operate beyond the reach of the local state, while avoiding being kidnapped in the darkness of night or bombed to smithereens by some of the world’s largest militaries. The money from this illicit trade could go to the Sudanese people to fund essential services like roads, health, and education. Instead, it is being used to beef up a murderous regime that seeks to establish their own state in Western Sudan at the very least.

The Rush for Sudan

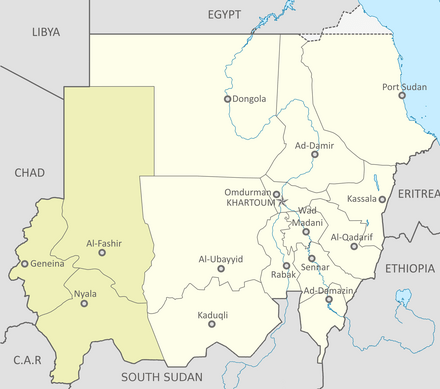

The Republic of Sudan sits on several reserves of natural resources in addition to gold and oil like chromium ore, iron ore, uranium, and manganese.(naturalresourceinfo, 2025) Sudan is also home to much arable land around the Nile, at least 180,000 hectares of it is already used to feed oil-rich Gulf nations.(Guo, 2025) Anyone who rules over such a resource rich terrain will be rolling in the dough no doubt. However, the two contenders must first overcome a comparable antagonistic military from within Sudan. Secondly, they must deal with the interests of the international community, not the least of which are the US and Russia with two polar opposite interests, as well as the UAE, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, among others. Thirdly, they must deal with an impoverished, traumatized, dispersed, and revolution-thirsty citizenry who have mentally checked out of capitalist military dictator rule. Finally, they must come to terms with a new global reality and decide which side they will fall on. They can either join the ranks of the Sahelian Alliance and BRICS who will manage their resources on their own terms or remain in the old neo-colonial order.

The demand for African resources is driven by Western greed for industrial gold, a critical component in the medical, electronics, automotive, and aerospace industries. Our smartphones, EV cars, and server farms (the backbone of Big Tech) come from unregulated streams of African resources. A destabilized Sudan comes just in a nick of time as the Sahelian Alliance nationalize their resources and wrangle themselves free from French and American neo-colonialism and as more countries see BRICS as a way out. Seeing that some nations are waking up, the West (primarily the US and Israel) is scrambling to weaken and divide unwitting nations to doubly exploit. Among them are the Sudan and Congo, but are soon to include the recently invaded Venezuela and other countries on their hit list.

Beyond manufacturing, gold serves as the ultimate insurance policy against the inevitable collapse of the US dollar. This collapse results from over a century and running of senseless wars, corporate bailouts, and overall mismanagement of the US economy by the American status quo. Matthew Miller, vice president of the CFRA financial research firm, stated:

…this debasement of the U.S. dollar is the biggest reason why central banks continue to demand gold at a high level, despite really gold prices continuing to go up. Central banks are big buyers.(“How Illegally Smuggled Gold Is Fueling The U.S. Gold Boom”, 2025)

Sudan’s crisis is a Westerner’s convenience. By allowing this gold to enter the global market as refined, “legal” bars in Dubai, which then exports gold to Switzerland (the world’s top gold exporter), the UK, US, and Hong Kong, we choose to ignore that it was mined amidst genocide and ethnic cleansing. As long as the global high-tech and financial sectors require these materials to safeguard their own futures, the incentive to prolong the conflict in Sudan will continue.

Conclusion

In the 16th century, the Portuguese sought African gold and slaves to solve their domestic “bullion famine” and finance their presence in the world market.(Solow, 1993) Today, foreign interests deepen the Sudanese crisis by supplying weapons to ensure their continued access to these resources. This cycle of violence and extraction sacrifices the lives, sovereignty, and well-being of African for the prosperity of the global capitalist class.

The modern scramble for empire is like a screen time addicted child desperately looking for a charger. If we are not aware of global supply chains and if we do not hold guilty parties accountable for their smuggling and convenient oversights, luxuries will continue to come at the expense of African lives as we watch their massacres on devices made from the materials they dug up. The tragedy of the war in Sudan is not that the world has forgotten it, but that the world is actively, and profitably, ignorant of it. For the Sudanese, the price is of genocidal proportions; more than 150,000 people have died and 12 million have been displaced. While diplomats and corporations remain silent and social and traditional media misinform, the mines remain open and the minds remain closed. In the meanwhile, criminals continue to carry their heavy, golden cargo to Dubai, Switzerland and beyond.

References

Booty, Natasha, Farouk Chothia, and Wedaeli Chibelushi. “Sudan War: A Simple Guide to What Is Happening.” Africa. BBC News, November 13, 2025. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cjel2nn22z9o.

Guo, Zihao. “UAE Land Grabs in Sudan and Famine Mitigation by Local Resistance Committees.” The Global Horizon, March 6, 2025. https://www.theglobalhorizon.press/studentfeature/view/uae-land-grabs-in-sudan-and-famine-mitigation-by-local-resistance-committees.

Pettitt, Jeniece, dir. How Illegally Smuggled Gold Is Fueling The U.S. Gold Boom. Produced by Comfort Woode. With Zinhle Essamuah. CNBC, January 16, 2025. 10:57. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3YWEy0ijeuo.

Soguel, Dominique, and Pauline Turuban. “Hidden Wealth: Swiss NGO Maps Africa’s Undeclared Gold Flows.” SWI Swissinfo.Ch, May 29, 2024. https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/multinational-companies/hidden-wealth-swiss-ngo-maps-africas-undeclared-gold-flows/79009684.

Solow, Barbara L. Slavery and the Rise of the Atlantic System. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press, 1993.

“Sudan’s Natural Resources: Locations, Discoveries, Viability, Export Potential, And Economic Impact.” Natural Resouce Info, April 29, 2025. https://naturalresourceinfo.com/sudans-natural-resources/.