There’s this thing where ethics aren’t what they used to be. This idea that people are trying to replace the ideas of good and bad with better or worse… and that is incorrect. You gotta keep your ethics intact because good and bad is a compass that helps you find the way. And a person that only does what’s better or worse is the easiest type of person to control. They are a mouse in a maze that just finds the cheese. But the one who knows about good and bad will realize that he’s in a maze.

Dave Chappelle at Allen University (South Carolina) March 20, 2017

I have paid close attention to every presidential election since the beginning of my adult life. Without fail, the debate ensues around voting for the lesser of two evils in many progressive circles. This is in lieu of any viable progressive rivals, who the American people are told are “unelectable,” a status that is reinforced by state-level interventions to keep them off the ballots. While the decision to vote for a softer, friendlier (usually Democratic) candidate seems to make sense in the moment, this reactionary strategy has only emboldened those candidates to become more evil and take the progressive (especially African American) vote for granted. Yet, the question remains: “at what point will we stop voting for evil?” While comedian Dave Chappelle’s words from 2017 may seem prophetic to some, the ideology of the lesser of two evils has been rejected by Ḥanīfs of ancient times, not the least of which appears in the story of Hārūt and Mārūt.

Hārūt and Mārūt

According to Imam Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūṭī in his book on angelology Al-Ḥabā’ik fī Akhbār al-Malā’ik, Hārūt and Mārūt are first alluded to in the Qur’an in al-Baqarah: 30 where we first encounter a conversation between God and the angels concerning the creation of mankind:

{وَإِذۡ قَالَ رَبُّكَ لِلۡمَلَـٰٓئِكَةِ إِنِّي جَاعِلٞ فِي ٱلۡأَرۡضِ خَلِيفَةٗۖ قَالُوٓاْ أَتَجۡعَلُ فِيهَا مَن يُفۡسِدُ فِيهَا وَيَسۡفِكُ ٱلدِّمَآءَ وَنَحۡنُ نُسَبِّحُ بِحَمۡدِكَ وَنُقَدِّسُ لَكَۖ قَالَ إِنِّيٓ أَعۡلَمُ مَا لَا تَعۡلَمُونَ}

˹Remember˺ when your Lord said to the angels, “I am going to place a successive ˹human˺ authority on earth.” They asked ˹Allah˺, “Will You place in it someone who will spread corruption there and shed blood while we glorify Your praises and proclaim Your holiness?” Allah responded, “I know what you do not know.”

The Clear Qur’an translation

The second allusion to Hārūt and Mārūt appears later in the sūrah in verse 102 concerning the false accusations of Prophet Solomon practicing magic. Hārūt and Mārūt warned people about practicing magic and taught people how to differentiate between miracles and magic.

“The Lesser Evil”: An Angelic Refutation

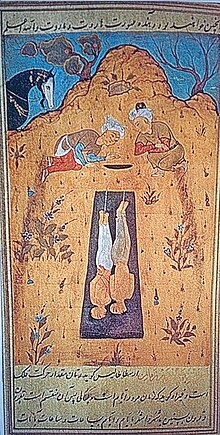

The backstory to these angels offers us some wisdom about the dangers of “the lesser evil” ideology. According to tradition, Hārūt and Mārūt were sent to earth where they ruled during the time of the Prophet Idrīs or Enoch. They were given the appetite and desires of people (shahwah) in order to test if they, who had once lived as angels, would behave differently when faced with the same temptations of normal men. Their story is as follows:

And it was said to them: ‘Choose from amongst you the two best angels and I will give the two of them a task; and I will prohibit the two of them [from doing certain things].’ And they chose Hārūt and Mārūt. So the two of them were sent down to Earth and the desires of the sons of Adam were aroused in them. [God] ordered the two that they should serve Him and not associate anything with Him. He banned them from killing prohibited individuals, from eating prohibited foods and from fornicating, stealing and drinking wine. The two remained on the Earth for a time ruling the people with justice. This was during the time of Enoch. And at that time there was a woman, who was the most beautiful woman, just as the beauty of Venus is amongst the rest of the stars. The two of them came to her, spoke softly to her, and wanted her on her own; but she refused unless the two took her orders and her faith. So the two asked her about her faith and she brought out to them an idol and said: ‘This is what I worship.’ And the two said: ‘There is no need for us to worship this.’ So they went and stayed away for a while. Then the two came to her and they wanted her on her own and she said as she had said before, so they went away. Then they came to her [again] and they wanted her on her own, and when she saw that they refused to worship the idol, she said to the two of them: ‘Choose one of three faults: worshiping this idol, killing this person, or drinking wine.’ And the two said: ‘None of these are right, but the least contemptible of the three is drinking the wine.’ So they drank the wine. [The wine] was taken from them both and they fornicated with the woman. The two then feared that the person would reveal what they had done, so they killed him. When the drunkenness lifted from them and they realised what sin they had done, they wanted to go up to heaven; but they could not, as it had been made inaccessible to them. And the cover that was between the two of them and between the people of heaven was lifted up, and the angels looked down at what had come to pass. They wondered with great wonder and they came to understand that whoever is hidden [from God], is the one with less fear. After that they began to ask for forgiveness for whoever was on the earth.

It was said to the two of them: ‘Choose between the punishment of this world and the punishment of the next.’ The two said: ‘As for the punishment of this world, it will come to an end and it will pass. As for the pain of the Angels and theology next world, it will not come to an end.’ So they chose the punishment of this world. The two stayed in Babylon and they were punished.

(Burge and Suyūṭī, 2012, pp. 94-95)

In this story, Hārūt and Mārūt were tricked into committing greater evil by doing what they perceived as a lesser evil. In reality, the lesser evil was simply a gateway into more evil. It was presented as a thing that would satisfy their immediate desire for drink and sustenance; something that is permissible under normal circumstances. However, compromising their principles by the seemingly innocent act of drinking the wine led to intoxication which led to committing fornication which led to murder. How many a prisoner sits in his cell pondering a similar scenario?

Conclusion

This story was intended to refute the Sabian position that gave favor to angels over men. It demonstrates that humans have favor because in order to avoid sin they must overcome their desires, while angels simply do not sin because they do not have such desires. However, there is also wisdom in this story for the average American voter who are forced to choose between duplicitous politicians of either the Democratic or Republican party. Politicians from the local to federal levels insist on doing the bidding of narcissistic, unethical, and devilish entities instead of the will of citizens who entrust them with their money and power. In choosing to stick with the status quo of Democratic and Republican party leadership we have taken that intoxicating sip that has put us on the path of destruction.

The 2024 elections have been a dirty game given the Republicans’ assassination shenanigans and the Democrats’ shiesty switcheroo. Both Democrats and Republicans have shown to be abetters of genocide and endless war, with blatant corruption among their ranks as witnessed in cases of Dem. Bob Menendez, Dem. George Norcross, Rep. George Santos, not to mention Trump himself. We at the Maurchives advocate for justice and non-violent, creative, and – dare I say – revolutionary solutions to human problems. Therefore, it is with the revolutionary spirit that we endorse Jill Stein’s presidential bid on the Green Party ticket.

References

Burge, S. R., and Suyūṭī. Angels in Islam: Jalal al-Din al-Suyuṭī’s al-Ḥabāʼik Fī Akhbār al-Malāʼik. Routledge, 2012.

Suyūṭī, Jalāl al-Dīn al-. Al-Ḥabā’ik Fī Akhbār al-Malā’ik. Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmīyyah, 1988.

Renshaw, Jarrett. “How US States Make It Tough for Third Parties in Elections.” Reuters, 18 Jan. 2024. http://www.reuters.com, https://www.reuters.com/world/us/how-us-states-make-it-tough-third-parties-elections-2024-01-18/.